Teach First Research Roundup: May 2022

We explore the effect of children's social and emotional health and wellbeing on their learning, using the concept of Whole Child Development and the latest research in education.

Have you ever struggled to concentrate because you’re too tired, or hungry, or cold? What about when you’re distracted by worries about a conversation or argument you’ve had with a friend or colleague? We all know that when we are ill or even just not at our best physically or mentally, we are less productive at work. The same is true of children and their learning.

If we are going to reduce the disadvantage gap in education, we need to also address the physical, social and emotional health and well-being of our children and young people. The links between physical and mental health are well known but it’s also becoming increasingly clear that learning is also linked to our social and emotional health and wellbeing. Two years of disruption to the lives and education of children has only heightened our awareness of issues that have been apparent for a long time.

Schools leapt to support families during lockdowns, going far beyond what should be expected, but what now? Poverty is rising, with a third of children now reported to live in poverty. How can schools best respond to these challenges? What support can we offer them? What more needs to be done?

If we want the best outcomes for children and young people, we need to re-evaluate what are often fragmented approaches and look at the whole child.

Contents

1. Whole Child Development (11 minutes)

2. Selected Research on Whole Child Development (3 minutes)

Whole Child Development

Whole Child Development as a concept in education has been in existence for decades, if not centuries, variously framed in terms of social-emotional learning (SEL), personalised learning, or child-led or child-centred. It is neither easily generalisable nor definable but in the absence of a universally agreed definition Teach First have decided to concentrate on four key principles of development: cognitive, physical, social, and emotional. We emphasise the importance of the link between development and wellbeing in and across these four areas as being tightly interrelated in leading to educational outcomes.

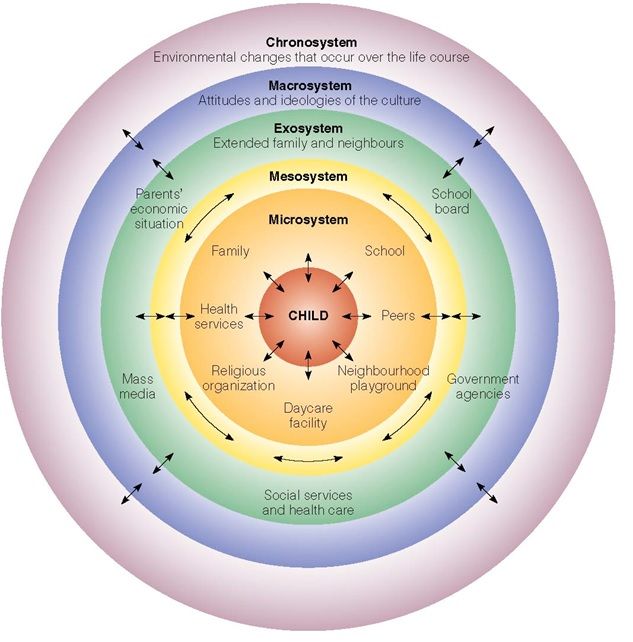

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1979) is a useful way of considering the complex system of relationships that influence child development and why schools play a significant role.

Figure from Guy-Evans, O. (2020)

This model can help us understand how different external factors interact and influence development. School is an important part of the microsystem that forms the everyday experience of a child as they grow and develop. But education does not take place in vacuum, and different elements will hold different significance for individuals – for example, the relative importance of religious organisation, or health services, the nature of their family, or their socialisation with peers. This also means that children will develop on different trajectories.

The real experts on child development in schools are in the early years. Here there is a clarity about the links between physical development, language and social development, emotional regulation development, and cognitive development – they are explicit and understood. A child cannot form letters before they’ve mastered appropriate gross and fine motor skills. A child that struggles to form attachments with other adults is likely to be dysregulated emotionally and unable to learn effectively. A child that hasn’t had opportunities to interact socially will struggle to understand turn taking or learning from their peers and find it hard to function within a complex society as they grow.

Modern psychology and cognitive science have told us so much about human development through childhood and youth. It is now widely recognised that the brain doesn’t fully mature until the age of about 25, leading to some reconsideration of how we understand adolescent behaviour. Research is beginning to help us understand how development might affect learning and what that means schools with a renewed focus on the science of learning helping teachers to unpick the factors that lie behind motivation and engagement and influence behaviour in and out of the classroom.

The challenge for teaching lies in unpicking age-related, or more strictly stage-related, expectations that may run counter the development trajectory of children across these four different areas. Development is not always linear nor does it follow a predictable timeline. It will be further complicated by any special educational needs or disabilities, as well as the environment in which the child lives and grows. Puberty, and the huge changes it brings, also happens at different times and rates and young people experience new challenges to emotional regulation and behaviour. Peer influence becomes ever more significant in comparison to adult, bringing with it the potential for engaging in more risky behaviours and pushing back against external authority. Even something like gaining enough sleep can become challenging for teenagers.

8 insights from our research to date:

- Headteachers and senior leaders believe that their schools support a culture of whole child development. This is a really positive finding that reflects a commitment from leadership to recognise the importance of social and emotional wellbeing alongside academic outcomes.

- Teachers are less in agreement that their schools support a culture of whole child development. It is common to find that teachers are not always in full agreement with what leaders believe is happening in their schools. There may be implementation gaps, or perception gaps. It is important to understand the challenges faced in the classroom and how we can support teachers effectively. Research from Teacher Tapp suggests that the vast majority of teachers view the teaching of social and emotional health and wellbeing as important.

- Poverty is a key driver of disadvantage in all areas and is a significant factor in predicting future outcomes in life.

- COVID has had a negative impact on all areas of whole child development, with those living in the most disadvantaged areas disproportionately negatively affected. For example, primary aged children living in the most deprived areas were more than twice as likely to be obese than those living in the least deprived areas. In fact, less than two thirds of year 6 pupils were a healthy weight in 2020-21 (National Child Measurement Programme, 2021).

- There has been no progress since 2011 in closing the attainment gap between persistently disadvantaged children and their more affluent peers (EPI, 2022).

- Mental and emotional health changes as children move into and through adolescence. The rates of probably mental health disorders in children have increased from one in nine in 2017, to one in six in 2020 (MHCYP, 2020).

- Poor mental health in adolescence is strongly associated with poor mental health in adulthood which can affect relationships, societal engagement and productivity (Crenna-Jennings, 2021).

- A Cambridge University study has found a positive link between physical activity and emotional regulation with a positive prediction on academic achievement through emotional regulation for 7-year-olds and behavioural regulation in 11-year-olds (Vasilopoulos and Ellefson, 2021).

What does this mean for Teach First?

We are working to make whole child development principles more explicit in our programmes to support teachers and leaders understand how they can support them in improving outcomes for students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. To do this we are engaged in curriculum research and development to inform our leadership and teacher training programmes, as well as raising awareness across the organisation and beyond. We are working with and alongside other organisations as part of the IntegratED partnership, to understand the challenges and opportunities to improve education for all pupils, but particularly those who are marginalised or face disadvantage.

Having a whole child development lens encourages us to consider how school cultures are experienced by all members of the school. Are there any whole school policies that might unintentionally discriminate against certain students or groups of students? For example, behaviour policies tend to be reactionary, but having a whole child approach might invite us to consider how we can be more intentional in our approaches and what strategies might be most effective for children at different stages of their development.

As part of developing our understanding, we are carrying out research in partnership with the University of Nottingham to help us better understand how schools and pupils conceptualise inclusion. What does it mean to them and what does it look like in practice? What tools and interventions can schools and leaders use to help them make their schools more inclusive?

Another area for future development is around tools that support schools in measuring the social and emotionally well-being of their students and evaluate how inclusive they are. FFT Education Datalab, as part of the IntegratED partnership, has developed the School Quality Index. This measures not only attainment but looks at proxies for inclusion such as attendance and exclusions. We intend to explore this and other tools further to help schools become more inclusive.

What does this mean for schools?

Everything starts with culture and values. A whole child approach means just that – a culture that values the whole child and is enacted in the daily life of the school. This involves both reflection and action. How does the curriculum support pupils – not just PSHE, but whole school policies around behaviour and learning, and the way the day is structured. Do children have time to eat? To socialise? What support is available to them? What impact does this have on learning?

One important question for school leaders is what outcomes do you measure? How far do these outcomes reflect your values? It is one thing to claim to have a culture that supports whole child development, but do you have data to support this claim and to help you identify and take action when it might be needed?

There is a balance to be found. Teachers are not social workers or educational psychologists, and nor should they be. There are many things we can do to support the wellbeing and development of children – developing their self-esteem, supporting their ability to self-regulate etc. But there is a line between typical and normal feelings of anxiety or sadness, and falling out with friends, and real mental health illness. The latter is for medical and mental health professionals to diagnose and treat. Challenge at a time when CAMHS referrals are exceeding their capacity to respond and support.

Schools that prioritise the emotional and social wellbeing of their students (and staff) see positive rewards in attainment as well. A school becomes a community where everyone feels as though they belong and where they can succeed.

Selected Research on Whole Child Development

The OECD published Beyond Academic Learning in 2021, results from a survey of social and emotional skills of learners at age 10 and 15. The findings include a dip in young people’s social and emotional skills as they enter adolescence but also that socio-economically advantaged students reported higher social and emotional skills than their disadvantaged peers in all cities participating in the survey. The research also suggests that social and emotional skills are strong predictors of school grades.

A nesta report from 2020, Developing Social and Emotional Skills, explores policy differences across the UK nations in relation to social and emotional skills and curricula frameworks. The report suggests that the existing competency orientated approach promotes individual responsibility which fails to sufficiently recognise the social context and importance of the role of schools and community in building young people’s sense of connection and identity.

The EPI have reported on COVID-19 and disadvantage gaps in England 2020. Whilst recognising the unusual methods of awarding grades during the pandemic has resulted in a small fall it he disadvantage gap at GCSE, they highlight tat the gap for persistently disadvantaged pupils has been maintained without substantive progress over the last decade. SEND pupils also faced a gap with a longer-term trend of slowing progress in closing.

Whilst now somewhat dated, this briefing from Public Health England for head teachers, governors and staff on the link between pupil health and wellbeing and attainment 2014, provides a useful overview of the evidence linking education and health. Drawing on a rapid review approach it highlights that pupils with better health and wellbeing are likely to achieve better academically, and that effective social and emotional competencies are associated with greater health and well-being, and therefore achievement.

Research carried out during the pandemic, Young people’s mental and emotional health (2021), also highlights that factors relating to socio-economic disadvantage are contributing factors in social and emotional well-being and mental health. The report also noted that low levels of physical activity and being overweight were associated with low self-esteem and well-being scores through adolescence. ImpactED also reported that regular exercise during lockdown meant pupils were more likely to have a helpful learning routine.

Vasilopoulos and Ellefson (2021) investigated the associations between physical activity, self-regulation and educational outcomes in childhood. They found a positive link between physical activity and emotional regulation across three time points – at ages 7, 11, and 14 years. Physical activity also positively predicted academic achievement through emotional regulation for 7 year olds, and behavioural regulation in 11 year olds.

We’d love to hear any feedback on our research series moving forward. To get in touch, please email research@teachfirst.org.uk.